You read that right: it’s SEGA’s first properly international console that would make for the best follow-up to its brace of Mega Drive minis, and not anything full of all those polygons. The Master System - initially 1985’s SEGA Mark III in Japan prior to its remodelling for worldwide release a year later - is unfairly maligned by many as a machine that’s inferior to Nintendo’s Famicom/NES, as a platform that lacked a substantial number of essential titles. But this perspective is completely wrong, which I’ll get into shortly. But let’s address what we already have for a moment, and then look at the system that so many are clamouring for a miniature version of.

Starting with the here and now, SEGA’s Mega Drive Mini II just came out, and it’s truly a diminutive bounty of retro beauty. Whereas the previous shrunken-down take on the company’s iconic 16-bit system, which came out in 2019, recreated the first design of the Mega Drive (Genesis, in North America) and folded in a heap of famous titles as pre-loaded attractions, this sequel bases itself on the squared-off second model and gets appealingly weird with some of its 60 included games. As well as a wealth of experiences that originally came on cartridges - including a few, like Streets of Rage 3 and Soleil (aka Crusader of Centy), that cost a fortune on today’s second-hand market - there’s 12 Mega CD games, such as the exceptional Sonic CD and infamous Night Trap. Master emulators M2 have also added all-new extras such as never-before-seen ports of Fantasy Zone, Space Harrier and VS Puyo Puyo Sun. Yeah, it only ships with one six-button controller; and yeah, the RRP of just over £100 is a bit much for one of these mini-consoles. But y’know, it’s worth it, with just the right mix of the known and the unknown, and a few slices of SEGA history that are practically unplayable otherwise (at least legally).

Advert

With two mini Mega Drives under its belt - and four super-tiny Game Gears exclusive to the Japanese market - SEGA is now asking its audience for thoughts on what its next mini-console should be. As reported at various outlets including VGC, buyers of the MD Mini II are being polled as to their preferences, with options listed including SEGA’s debut console of 1983, the SG-1000, and its home computer variant the SG-3000; the SEGA Mark III and its international redesign as the Master System; the 32-bit Saturn and its successor, SEGA’s final console, the Dreamcast; and either more arcade-styled hardware in the manner of the Astro City Mini (and V) or a third Mega Drive release, because why not. A lot to pick through, and a lot of history - but there’s really only one viable option for the next SEGA mini right now, and it’s not the Dreamcast.

Don’t get me wrong, I love SEGA’s swansong when it comes to pre-minis home console hardware. The Dreamcast was a beautiful thing that burned out too fast, its forward-thinking design undeniably inspirational on both Sony and Microsoft. But the Dreamcast was doomed before it even came out, SEGA’s financial foundations creaking after the rotten worldwide sales of the Saturn, a system that senior staff at the company publicly stated they couldn’t wait to move on from. Whatever advances in home gaming the Dreamcast delivered - more accessible online play, the use of a second (removable!) screen for select games, open-world adventures the likes of which we’d never seen with Shenmue, and legitimately arcade-perfect ports of celebrated coin-op bangers - it began life on the backfoot in 1998, overshadowed by the PlayStation's dominance through the second half of the 1990s, and it was obliterated by the PlayStation 2 even before that console came out, buyers holding off spending on SEGA’s machine in anticipation of Sony’s behemoth in waiting.

In short, the Dreamcast was dead on arrival. However, the amazing odds the console was up against when it launched, plus the genuinely great software released for it (some of which remains easily playable today on Steam and other platforms), has ensured it has this mystical air about it, a supremely positive legacy that might have been so very different had more people actually bought it at the time. Given that the Dreamcast is where SEGA games of old most resemble the games we play today, in their ostensible design and visual characteristics, it’s somewhat natural that this is what younger players want to see made into a mini next. And I cannot deny that a compact console complete with a pretend VMU and built-in games like Jet Set Radio, Crazy Taxi, Rez, Metropolis Street Racer, Sonic Adventure (and its sequel) and Shenmue one and two would be terrific. But it doesn’t make as much business sense as the Master System, right now.

Advert

So let’s get into that. Firstly, think about why SEGA led with the Mega Drive. Many of its games are available today either as individual downloads through the SEGA AGES range, as an expanding set through the Switch Online service or what feels like countless compilations going back to the 16-bit era itself. Pick a console of the last 20 years, and there’s probably a Mega Drive collection for it. So why give people all of that again, in a little plastic box shaped like the OG console(s)? Basically, nostalgia sells. The Mega Drive hardware is super recognisable, more so than the Saturn or Dreamcast, because it sold in far greater numbers than both subsequent systems. Overall sales for the Mega Drive/Genesis across official SEGA models and the subsequent Tectoy and Majesco releases are around 35 million at lower estimates and as high as 47 million, globally. That’s a lot of older, perhaps lapsed players in their 40s now who’ll get excited to see this hardware come back. But both Saturn and Dreamcast sales fall under 10 million worldwide, so that same large potential audience just isn’t there in raw nostalgia terms.

Looking at the Master System’s global sales, the number is around twice that of the Saturn and Dreamcast. Indeed, it’s more comparable with the two later-released consoles combined, at just under 20 million when factoring in the Tectoy releases in South America on top of official SEGA models. (And if you don’t know what I mean by Tectoy models here, that’s a whole other rabbithole for another time.) Ergo, that’s a much larger audience of people who will have used this console in their childhood and will be attracted to a simple plug-in-and-play version of it pre-loaded with a stack of games, some of which they’ll know and some they won’t. Younger players might prefer the experiences a Dreamcast can offer over the 8-bit limitations of the Master System, but all of these things are emulatable nowadays, and it’s the oldies, if you will, who are more likely to shell out for a premium product than those already familiar with getting such things for free. Playing a numbers game, coldly and objectively, the Master System is the more viable mini than either the Dreamcast or the Saturn.

There’s a twist here, too - while the Master System did outsell the Dreamcast and Saturn, even before adding Tectoy’s range, it did so with incredibly limited performances both in Japan and North America. In those markets the Master System - and Mark III - remain platforms that are somewhat unknown to a large audience, enigmas of the 8-bit age that Wikipedia-based histories on the period have pigeonholed as being inferior to what Nintendo was selling at the time. This gives SEGA something of a point to prove: that the Master System really wasn’t the poorer of the two ‘console warring’ machines (let’s not forget that Atari was still active in the mid- to late-1980s, albeit as a diminished force, and the PC Engine was a big deal in Japan, so this was never a two-horse race). And it’s an overdue ‘actually’, because the Master System’s NES-beating success in Europe wasn’t simply down to better marketing - in some ways, it was the better console.

Advert

When it came to on-screen colours, the Master System could produce more than the NES, 31 simultaneously from a palette of 64 compared to 25 from 56 (doesn’t sound a lot today, but compared to what we had before this made the Master System’s graphics look unreal). The Japanese Master System’s Yamaha FM sound chip also made the NES’s Ricoh feel lightweight. And while the two systems shared several design elements, right down to the two-action-button controllers with their D-pads, the Japanese Mark III incorporated backwards compatibility with the SG-1000, giving players in that region access to more primitive-looking but nonetheless immensely fun games - including the first title worked on by Sonic the Hedgehog designer Yuji Naka, Girl’s Garden, and ports of SEGA arcade games Zaxxon and Flicky.

Perhaps you can see where this is heading. With many of these minis including some value-adding extras, a Master System Mini (modelled after the Mark III for Japan, perhaps) could incorporate SG-1000 games alongside the ‘standard’ array of 8-bit inclusions. This would unlock a period of SEGA history not widely known to Western players, connecting the dots from franchises that were born in the 1980s and 1990s but still have a high profile today - most notably Sonic the Hedgehog - to where it all started for SEGA’s home gaming hardware, and some of its most celebrated designers. I appreciate this is a bit of a niche thing for any new mini’s list of wants, but with the MD Mini II giving us so much more than Mega Drive games we already know so well, I can see it happening. And I’d really welcome it, too, as the only easy ways to play SG-1000 games otherwise are, let’s say, on the shady side.

Turning the Master System timeline around, a mini would also allow SEGA to showcase what the console was capable of in its later years, as its official discontinuation didn’t arrive in Europe until 1996, after the Saturn and PlayStation were already in stores. In Brazil, the platform technically isn’t discontinued at all, and fully licensed software was released on carts in that territory as late as 1998. The SEGA-developed, Mickey Mouse starring Legend of Illusion came to the Brazilian Master System in that year (having previously released worldwide for Game Gear), and there were other familiar names popping up in the late ‘90s: Street Fighter II, Earthworm Jim and Sonic Blast in 1997, and FIFA International Soccer and Mortal Kombat 3 in 1996. These games (and many more besides) didn’t release anywhere else in the world for Master System, with PAL support ending with The Smurfs 2 in 1996 (the one game released that year) and the final North American game being 1991’s Sonic the Hedgehog. Suffice to say that several other markets have some enjoyable catching up to do if a Master System Mini looked to South America for a few selections.

Advert

While the first 8-bit Sonic - not simply a stripped-back version of the Mega Drive game, but its own beast developed at Yuzo Koshiro’s studio Ancient - was the final Master System game in North America, SEGA’s mascot earned further home and handheld 8-bit releases elsewhere, and it’s fair to say that his makers haven’t done a whole lot to celebrate those typically pretty darn good games lately. We’ve had Sonic Origins pulling together the 16-bit first, second and third games with some added CD action, and the MD Mini II includes the isometric Sonic 3D: Flickies’ Island, but the 8-bit games are overdue their chance to shine again.

A Master System Mini could - and likely would - feature not only the first Sonic for the platform and its 1992 Aspect-made sequel but also 1993’s Sonic Chaos and - because why not - the Game Gear’s Triple Trouble, Sonic Blast and one of the very few games to feature the hedgehog’s sidekick in a leading role, Tails Adventure. Given the Game Gear is essentially just a portable Master System on the inside, folding these games into an 8-bit Mini should be simple enough - even if they’re hidden away as unlockables, perhaps.

The Master System is (was) more than just Sonic though, naturally - the blue blur didn’t spin his way onto the console until 1991, six years after the Mark III’s debut. While SEGA’s system couldn’t really deliver the full-on arcade experience of its many successful coin-ops in the home - that kind of parity wouldn’t arrive until the Dreamcast and its architecturally comparable NAOMI arcade hardware - it did a lot with what it had to deliver superb takes on Hang-On (which was built into some models), After Burner, Alien Syndrome, Space Harrier, Out Run, Altered Beast and Golden Axe.

Advert

It’s easy for anyone who didn’t play these obviously compromised conversions at the time to conclude that they’re clearly not as good as the actual arcade games which are so effortlessly emulated on 21st century systems, but that’s missing the point. At the time, this is what we had, and we loved them. It felt amazing to have After Burner at home - because, be fair, you’re never fitting that Terminator 2-featured lump of a machine into your average-sized living room. And many non-SEGA arcade games fared better on the Master System than they did the NES - just run Paperboy or Double Dragon side by side, MS to NES, and you’ll see that clearly enough, those extra colours doing a lot of work. Played today, these are artefacts of wonder, impressive demonstrations of what skilled developers could achieve with minimal horsepower under the home-console hood. They can’t and shouldn’t be set in parallel to later ports for more powerful systems.

Discovering games from outside the realm of what you already know is a huge element of the appeal of mini-consoles - to me, and surely I’m not alone there. So it’d be likely that as well as all of the above SEGA-originated games, a Master System Mini could spring some brilliant surprises, reminders that the platform did have software that could compete with anything on the NES. I’m not saying that the library for the Master System is better than what Nintendo was working with in the 8-bit years, given it provided a home to Super Mario, Zelda, Metroid, Castlevania and more, but any claim that SEGA’s competitor didn’t have superb games of its own is one that comes from a position of utter naivety.

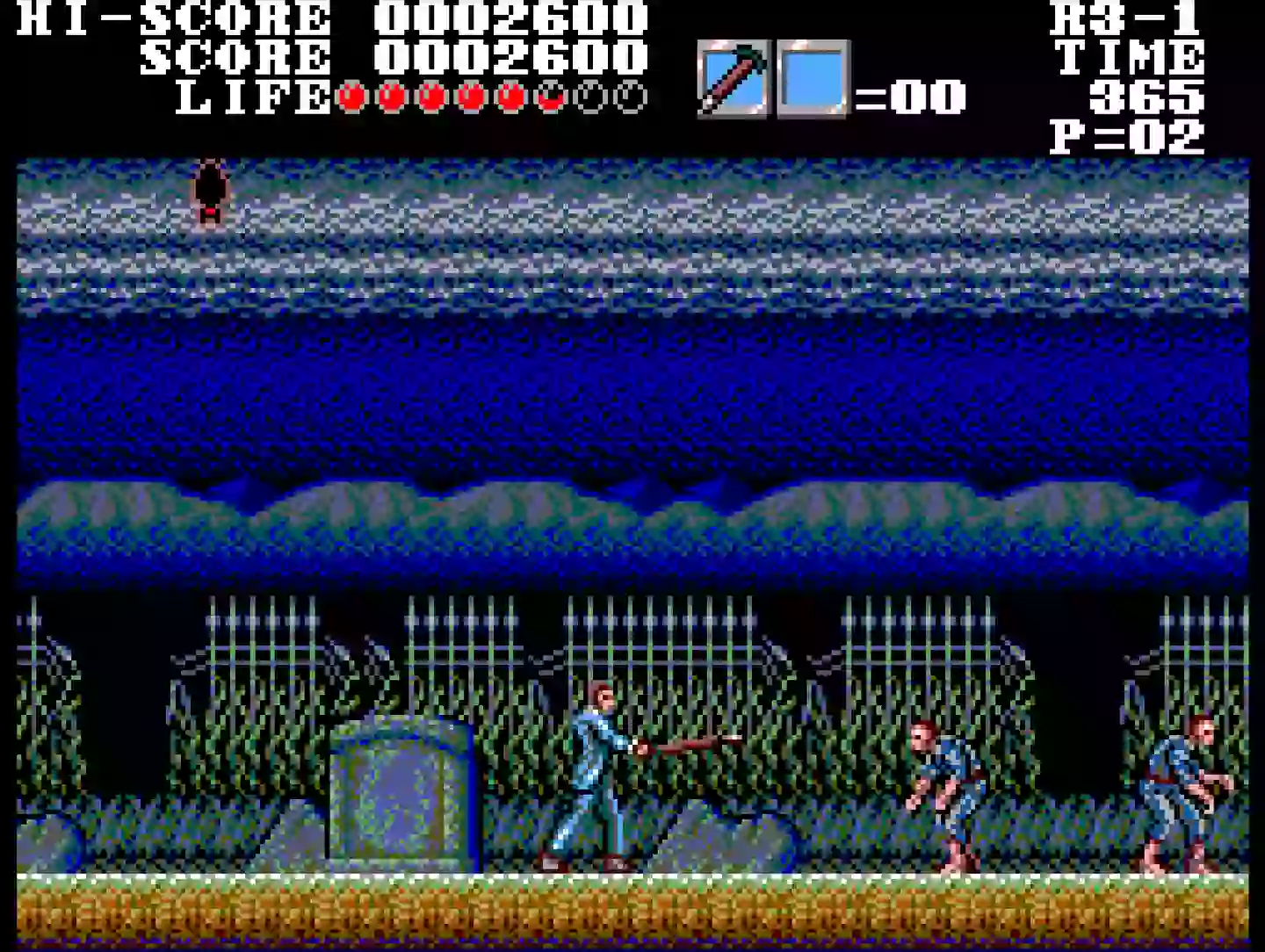

Those who’ve played their way through some of the Master System’s well-acclaimed releases will already know all about its amazing port of Road Rash and the sumptuous Metroidvania (before that was even a thing) of Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap, one of the best 8-bit games of all time. But there’s also Master of Darkness, a vampire-themed side-scroller that’s typically referred to as SEGA’s own Castlevania (and it’s just as good, although a whole lot weirder); the Zelda-like Golden Axe Warrior, which provided a nice deviation from that series’ hack-and-slash action; the shape-shifting platformer Psycho Fox, which has remained exclusive to the Master System (and commands a pretty penny second hand); and Alex Kidd in Shinobi World, the best game starring SEGA’s pre-Sonic mascot which parodies the ninja shenanigans of the other series in its title quite superbly. So throw all of those onto a Master System Mini please, SEGA, and expect to open more than a few eyes to just what this machine could do in the right hands.

So that’s original sales, stronger nostalgia potential amongst actual buyers, a more than solid library of recognisable games, and the draw of the wholly unexpected (and the historically important): reasons enough, I think, for SEGA to be looking at the Master System and Mark III as the next step in their journey into minis. Such a release wouldn’t rule out a Dreamcast Mini in the future, or a Saturn Mini, and could even build confidence at the company that such lesser-loved (in their times) hardware could translate to the HD-ready, fully loaded miniature format. Nintendo’s NES Classic Mini went down a storm, so I say: SEGA, be bold. Dare to rewind to an age of gaming that many reading these words right now will have no past connection to, and finally confirm for those who only know their gaming history through YouTube videos and unverified wikis that the Master System really was a platform that played with staying power enough to be just as well regarded in the 21st century as its Mario-supporting main rival.

Topics: Sega, Retro Gaming, Opinion