The idea that video games can be used as a genuine force for change is still considered an outlandish notion to a surprising amount of people.

This, despite the fact that there are more gamers of all ages and backgrounds than ever before. This, despite the fact that the video game industry is more profitable than the music and film industries combined. It seems as if there will always be those who see games as dangerous wastes of time that turn kids’ brains to mush and encourage them to become violent killers. Quite how you can go on a murderous rampage with a head full of mush is beyond me, but I suppose video games find a way.

Video games are bad for you. That’s what we’re still told on a weekly basis, in spite of an increasingly hefty pile of reports and studies to the contrary. Are they perfect? No. Are they absolutely blameless in the way they can influence our behaviour and mental health? I don’t think so. But they can be used in positive and meaningful ways. We just need to start looking in the right places.

Catherine Knibbs is, among many other things, a child, adolescent and adult trauma psychotherapist. Over the last decade, she’s strived to embrace technology in her work, using her background in cybersecurity and data protection - not to mention her inherent love of video games - to introduce gaming into her therapy sessions.

Advert

Technology is a fundamental part of kids’ lives today. I’m 28, and when I was growing up internet access was still limited to hour-long sessions in the evening (two hours on the weekend, lucky me). For a lot of kids around the world these days, the internet is everywhere. It’s all the time. An inescapable fact of life. Like Nandos, or Coldplay albums. Catherine chose to see the positive potential in this, and took the opportunity to connect with her clients on a deeper level.

“A lot of people will engage in activities that help them feel part of a team,” Catherine tells me. “And around 2012, I started to listen to what younger people were doing, and I thought; ‘okay, there has to be a way that I can bring this into the therapy room.’”

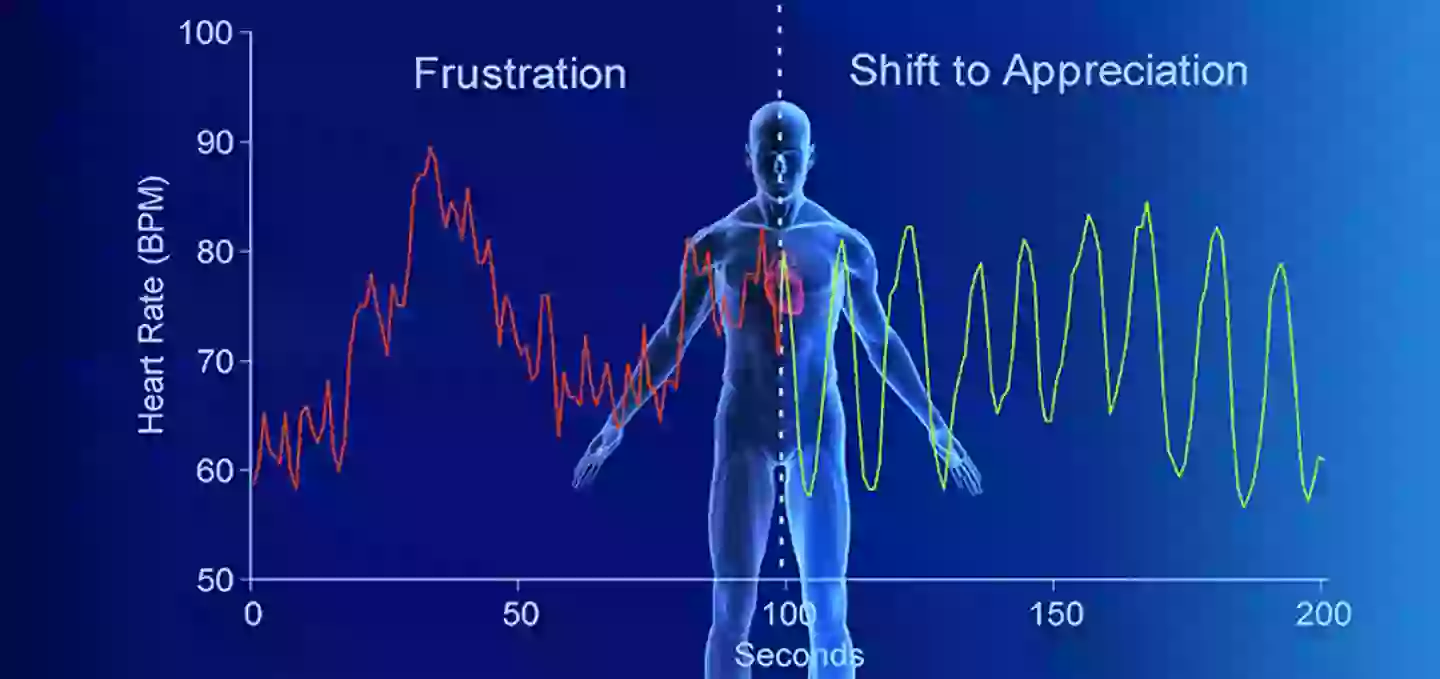

Catherine started by downloading a number of systems from HeartMath, a company that creates apps designed for helping to monitor stress levels and assist in relaxation, breathing, and mindfulness. Before long, she noticed that many of the children she worked with would “gamify” the breathing exercises. From there, she would transition onto the computer, where a number of specially designed interactive exercises were waiting.

Advert

“It’s so easy to say, ‘how do you fancy playing a computer game that's not like all of the others?’” Catherine explains. “And to watch a child master it… the adults take ages to get where the children are! But the younger children immediately knew what they needed to do.”

As someone who has been in and around the gaming industry, with a genuine love of games herself, Catherine started to include more traditional titles into her work. As you might expect, there’s a greater focus on slightly more “relaxed” video games. Things like Minecraft and LEGO Star Wars are more likely to be used in her sessions than Dark Souls or Call Of Duty. This, she tells me, is mostly because she has very strict rules when it comes to allowing her clients to play age-appropriate titles while in her care. But even speaking with clients about the games they want to play but can’t can be just as enlightening as actually playing them.

“I have an enormous chunk of games that are rated 16 or 18,” Catherine says with a smile. “And I purposefully have them in the room because they're my games. I’ve got Halo, Call Of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, to name a few. All of these games allow me to have a conversation with the children.” I can ask them which games they like, and what they like about each specific game.”

While explaining to some children that they’re not legally allowed to play a game like Grand Theft Auto V or Call Of Duty: Warzone during a session can often result in an argument, Catherine tells me that once they settle into the more family-friendly titles, the benefits are evident.

Advert

_NVIDIA.jpg)

“Most of the games have the same element in terms of therapeutic relationship,” Catherine says. “A lot of people that I work with are traumatised, so being able to not directly look at that person is helpful. So sometimes I will sit alongside them. So they could choose to use the PS4, or the Xbox or the VR headset. And then we have a discussion about what games there are. And then I can talk with them, alongside them, I can talk to them about what they're doing, I can support them in their cognitive development.

“Let’s just use Minecraft and Rocket League as examples. So these are two really different games, but the same thing occurs with the children: they will either systematically approach the problem, or it's erratic. And that helps me understand their thinking processes. I can understand how they manage distress tolerance, I can look at the way they're breathing. So I will often reply to them, and say to them; ‘you know, I've noticed when you're shooting up the side of the wall in Rocket League that you're holding your breath’. Or ‘when you're mining, you get four or five blocks down, and then you start to get excited about what you're doing next.’

“And so I'm picking up all the time on the environmental cues that allow me to do my work. I'm looking at what's happened to them in terms of their story. And then the game allows me to help them describe their issues more clearly. It looks like we're playing. But of course, there's a lot more to it.”

Advert

I found myself particularly interested in why speaking through trauma is easier while sitting next to each other playing a game. As a card-carrying emotionally repressed human man with severe anxiety, I immediately understood why this might be more palatable for Catherine’s clients. I know it’s become something of a meme among male gamers, but it is easier for a lot of people (men in particular, in my own experience) to talk about “real” issues while using a video game as a buffer. I’ve had shockingly deep conversations about grief and loss while playing Super Smash Bros. Melee, for example, and would often speak with a friend about our shared pandemic-induced fears over Call Of Duty: Warzone. Why do so many of us find it easier to talk this way?

“It's non threatening,” Catherine explains. “The eyes are actually part of the brain. So when you're facing something head on, like we are right now your eyes will go into what's called convergent vision, so they kind of ignore the periphery. And that often signals danger to the part of the brain that's involved in threat detection.

“And for most clients, it's really difficult for them to look you in the face because they feel whatever happened to them is shaming, and shame is also a physiological dysregulation… so it becomes this space where if I've had an interpersonal assault, or I've had an interpersonal issue, such as domestic abuse, then I don't want to be staring at you because you could feel threatened. So sitting alongside somebody is exactly what we used to do as youth workers. We’d sit in a car, or go for a walk - anything that doesn't feel like you're going to be attacked.”

Advert

But while Catherine has been implementing video games in her work for over a decade now, it’s yet to establish a mainstream foothold. There are, she believes, several factors involved here. Crucially, it boils down to a lack of understanding of what video games can be and how they can be used - a lack of understanding that has only been compounded by mainstream press coverage that consistently treats video games as the constant cause of - rather than the solution to - issues facing young people.

“If I just talk about the therapeutic profession, we are on average, so anti technology. Because we're taught to talk to real people in the corporeal world, as I call it” Catherine reasons. “And of course, we were forced to do this online stuff in lockdown, and most of that was me arguing with people and saying: ‘this is technology you need to be using.’”

“And I totally agree that the media spin plays a part. I get this. If we can demonise something and make that the issue, then we don't have to take personal responsibility. And what I'm finding at the moment, and I'm just thinking about one of the Facebook groups that I'm in, parents are so punitive that they’re using words like ‘addiction’. We don't say this about other sports. We don't say ‘David Beckham is addicted to football’. We say he’s studious. He practises. He's an expert.”

Partway through writing this article, something interesting happened in the world of video games. DeepWell Digital Therapeutics - a newly founded company aiming to develop and publish video games built from the ground-up to be used in therapy - was announced.

Described as the “first of its kind”, DeepWell’s mission is to create “best-in-class gameplay that can simultaneously entertain and deliver, enhance, and accelerate treatment for an array of globally pervasive health conditions”. In other words, it quite literally believes video games are the best medicine, and wants to make games of all genres to change lives.

DeepWell is the creation of Devolver Digital co-founder Mike Wilson and Medtech innovator Ryan Douglas. Together, they’ve assembled a team of experts from the fields of gaming and medicine, all united in the belief that video games can be good for you.

“DeepWell are clearly thinking about the use in many therapeutic settings where games can be brought to those in need, perhaps circumnavigating the need for people to visit practitioners via physical or geographical travel,” Catherine told me over DM a few days after the company was made public.

“Games can be shared experience, Co-created with the intervention and outcome in mind as a playful and pleasurable experience for the client/patient. I am keen to see the games developed here, backed by science and research and sprinkled with that element of fun that games bring.”

Having also spoken to Mike about his aims and hopes for DeepWell, it’s clear that he and Catherine are very much aligned in their thinking. There are, it seems, a growing number of professionals who can see video games are a substantial part of the future of medicine. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t still work to do.

Helping parents to better understand why their kids play and what they get out of it is essential, Catherine tells me. During lockdown, I spoke with a number of older parents and grandparents who were able to use the time inside to get into games in a way they might never have done otherwise. These are older folk who never would’ve gamed who, amazingly, became obsessed with the likes of Red Dead Redemption 2 and Call Of Duty: Warzone. Through simply picking up a pad and engaging with their family members who were gamers, they started to see the joy in it. Catherine believes that parents should absolutely get involved, because seeing why your child games and understanding what they get out of - the good and the bad - can be of huge benefit to all involved.

“I try to explain this to parents, that there's also a social element to games,” Catherine says. ”And this is what I talk to the children about. How do you know who you're talking to when you’re in this game? Tell me what it's like that I'm cheering you on? So often, I can sit alongside them and it allows me to demonstrate that it's okay to lose, we're not all always going to be that esports winner. I think this is where that media issue sits at the moment. That it's addictive. That people will have heart attacks. But if people understood child development, as well as peer relations, they would actually start to see that there's a real need for these young people to be with their peers, and where their peers are, is online. So you know, I am an advocate for it. And yes, there are times it can get in the way of family life. But that is usually a family based issue, not a gaming based issue.”

With a background in cybersecurity in addition to her work with young gamers, Catherine understands that it’s entirely possible for toxic online environments such as in-game lobbies to lead to serious issues, especially for younger gamers. How, then, does she explain to concerned parents that video games can be the solution as well as the problem?

“A lot of the time when I'm speaking with parents, there’s usually been an incident,” she says with a sigh. “That's why their children are usually in my office. But this is why I'm writing books. It's why I'm trying to educate teachers, and designate safeguarding staff. It's why I'm aiming at the professionals rather than just the parents. Because understanding how to set privacy settings is probably the most important thing that you can do with your child and explaining that you're not being punitive.

“The metaphor that I always use is the public park, okay? You do not send your child into a public park without knowing the pathways, having taken a walk there yourself. We would educate our children. But parents often don't understand the gaming space. And they will allow their children to go into the gaming environment thinking that they're playing with people their own age. And of course, they don't necessarily understand the dangers.

“And the dangers might be that wherever there are children, there are adults posing as children, which you cannot do in the real world. Some of the conversations being had in these spaces are way beyond what that child may well have learned in their family dynamics, such as sexual information, information about using technology, foul language, and bullying tactics.”

It seems almost too simple a solution, but Catherine tells me that parents who just sit down with their kids and try to get involved with what they’re playing can uncover a world of understanding they might previously have lacked. They develop an eye for the dangers they need to protect their children from, as well as the fun they can share in.

“When some of these players are taking headshots at kids on purpose repeatedly, it is no wonder they're gonna rage quit,” Catherine says. “And of course, the parent only ever sees their child, they don't see the context behind it. Ask them questions. Listen to the conversations that they're having. You would stand at a football match and watch your child to understand the rules, even if you didn't like football. It's a difficult one without sounding like I'm pointing fingers. But social media companies and gaming companies have created an environment where parents don't necessarily fully understand - or want to fully understand - what's happening.”

Education and conversations. That’s what Catherine keeps coming back to when I ask her how we can move forward. Even now, she’s working to encourage those conversations. Not just between families, but with organisations and peers. But even as Catherine and others like her attempt to find new ways to embrace technology in therapy and get others to do the same, she believes it’s only a matter of time before opinion shifts and video games are a more widely accepted tool for meaningful communication.

“I reckon that the 25/26 year olds now are going to be dealing with this very differently in the next 20 years or so,” Catherine says hopefully. “They've grown up with this technology and they understand it. We've just got this gap at the moment.”

One way or another, it seems video games do have their part to play in shaping the next generation of therapy. We just need to be willing to listen - and learn.

Topics: Mental Health