“I don’t think it’s a political game.” These were the words of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare campaign director Jacob Minkoff when discussing the then-new game with Game Informer, in 2019. Not a political game. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare - a game with a campaign plot that sees Russia edging close to war with a (fictional, in this case) Eastern European state, that features a terrorist organisation called Al-Qatala, that features a ‘Highway of Death’ absolutely not inspired by this very real one in the Middle East, which may or may not have been the scene of Actual War Crimes. Not political.

Continues Minkoff: “The question, ‘Is this a political game?’, doesn’t mean anything. Do we touch topics that bear a resemblance to the geopolitics of the world we live in today? Hell yeah. Because that is the subject matter of Modern Warfare.” Thirty-two seconds into the interview in question, or the video edit of it anyway, and a developer, terrified of coming out and saying yes, our game is political, d’uh, has utterly contradicted himself. You don’t need to specifically say: this game is based on this thing, this place, this event. The themes speak for themselves, and while the locations might be fictional, we haven’t fallen for this our game’s not political rhetoric since the days of Desert Strike and its not-at-all-based-on-Saddam-Hussein dictator, the unsubtly named Kilbaba. If not long before then.

Advert

I understand why. Call of Duty is a massive franchise. One of the biggest in video gaming. How well it sells every year has a huge impact on its publisher’s bottom line. In 2022, the annual CoD is Modern Warfare II (note: not ‘2’, as that game came out in 2009), and it has some work to do after 2021’s entry, Vanguard, failed to meet sales expectations. If you’re a spokesperson for a series like Call of Duty, you simply cannot afford to alienate a potentially substantial part of your audience. And in gaming right now, there persists a seemingly sizable section of players who will post beneath any article discussing politics in video games, or simply stating a stance that most common-sense-minded folk would agree is A Good Thing: keep politics out of my video games.

We’ve all seen those comments before. Some of you reading these words, right now, may even have written them. But here’s the thing: just like music, movies, literature, art right across the expressive spectrum, video games are informed by the lives of the people who make them. They are part of the real world we walk through every single day, albeit often framed within a filter of make-believe and prone to flights of fantastical exaggeration. And politics are everywhere. Can’t move for them. That could be close-to-home stuff, like how your block is the last to get upgraded to faster internet because of some local borders technicality that dates back three decades; or global-scale situations, like Russia’s ongoing aggression in Ukraine (and elsewhere), the unsalvageable mess that is the present British Conservative Party (your views may differ, but mine are set), or anything else that hits the national and international headlines. And I can guarantee you: whether anyone on the development team states it explicitly or not, the next Call of Duty will be looking at those same headlines, and taking inspiration from them. It is modern warfare, after all.

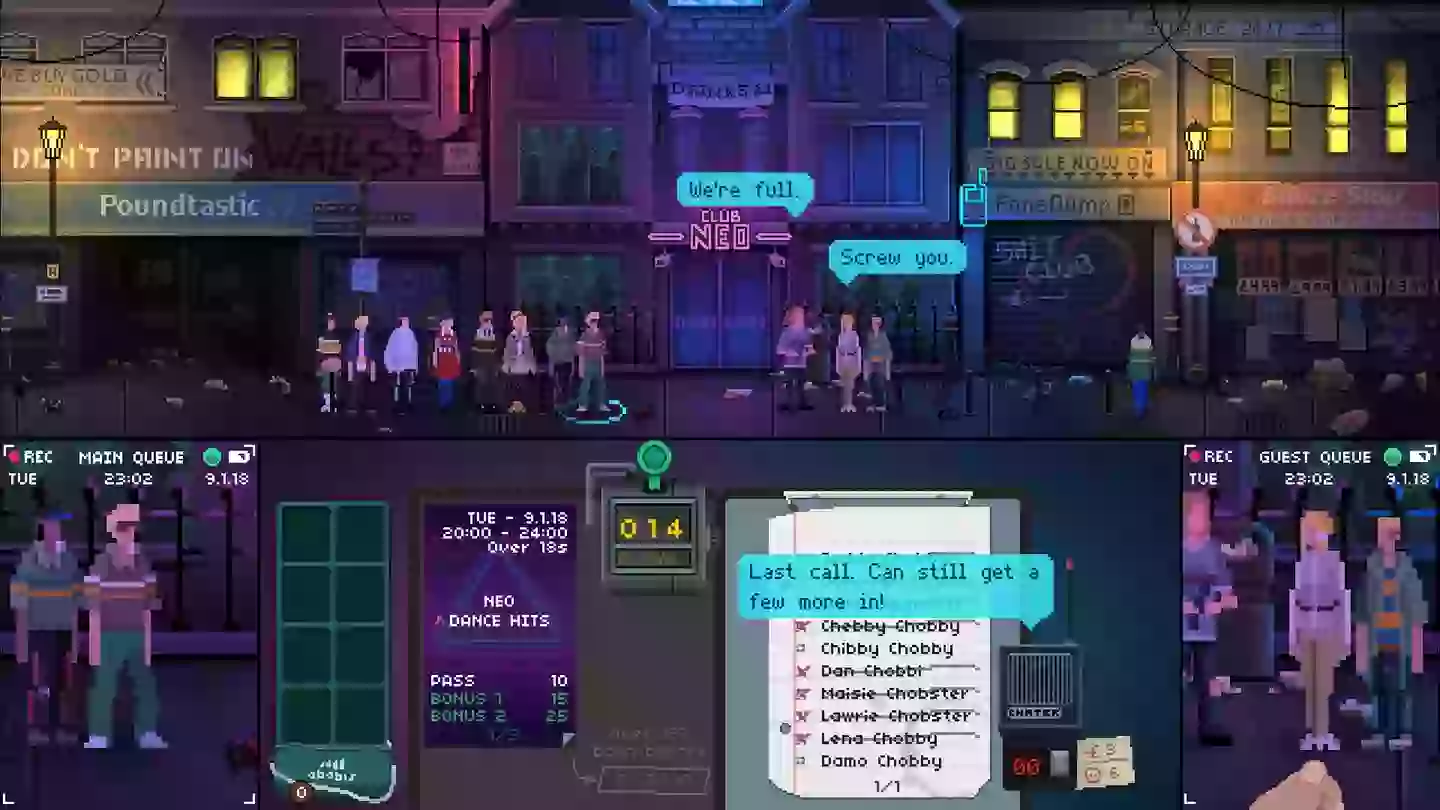

Check out the launch trailer for 2022’s Not Tonight 2, below

“It is not possible to keep politics out of games,” Tim Constant tells me. He’s the creative director on Not Tonight - a post-Brexit game set in an ostensibly fictional UK where the government has slipped to the far right and is manipulating the population (sounds completely farfetched, doesn’t it) - and its sequel, set in a “broken America”. “Anything creative will have a bias,” he continues, “even if it’s not explicitly created to be political.”

Advert

Tim’s games, developed at the studio PanicBarn and published by No More Robots, clearly are meant to be perceived as explicitly political. That’s something that was sewn into their very fabric, presented to the fore in their marketing. Often though, a game’s politics are spoken quietly, part of the story, there if you want to look for them but not highlighted. However, they are most certainly there, and to deny them is to be naive in the extreme. One such game is Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption 2, which Tore Olsson, associate professor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, has woven into his lectures on American history and its changing political landscapes and movements - something that was “quickly embraced by my department and the university’s leadership”, which is something other academics could take a note of.

- - -

“Americans tended to wear their politics on their sleeves in the late 19th century, and most outlaw gangs had very obvious political identities.” - Tore Olsson

- - -

Advert

“The Red Dead Redemption games depict topics that have been the source of tremendous debate and disagreement amongst historians,” he explains. “The Mexican Revolution, the expansion of corporate capitalism, the post-Reconstruction ‘New South’, the commercialisation of Appalachia, the Indian Wars, and many others. In portraying these topics, it’s impossible for the games’ developers not to have chosen sides in how they portray them.”

Which is to say that Red Dead Redemption 2, and its predecessor/sequel (yeah, it’s confusing when it’s put like that, huh), is a hugely political game, with the biases of its makers evident in how its story plays out, and the actions that protagonist Arthur Morgan participates in. Olsson continues: “The games have a pronounced anti-corporate bent to them, having little but disdain for ‘robber barons’ like Leviticus Cornwall - a fictionalised composite of men like Cornelius Vanderbilt and Andrew Carnegie. Which is ironic, given that the creators of the game are employees of a large multinational corporation.

“But for all the political decisions made in the creation of the RDR games, there is actually little explicit discussion of politics by the games’ protagonists. No game character, at least by my memory, confesses a partisan identity, whether Democrat, Republican, Populist or other. In reality, this would have been extremely rare - Americans tended to wear their politics on their sleeves in the late 19th century (Red Dead Redemption 2 is set in 1899), and most outlaw gangs had very obvious political identities. For example, the James-Younger gang were noted Democrats. Wild Bill Hickok, in contrast, was a noted Republican.”

Advert

But while Rockstar’s developers might have done Arthur Morgan and John Marston something of a disservice by not making them more passionate about politics, it’s easy to understand why they only skirted significant issues of the time, hiding perspectives beneath satire, beneath fictionalised individuals serving as vessels for muted commentary. And why they do the same in the Grand Theft Auto series. Quite simply, the outcry of keep politics out of my video games will not go away, despite the frequent words - words like these - outlining just how futile such protests are. The Guardian said as much in 2018. Eurogamer in 2019. The Financial Times in 2020. It turns out I already wrote a piece a little like this one in 2019, but it died in the migration from LADbible’s website to our dedicated GAMINGbible home (not intentional, and I’m pissed - but you can read it on this other site, not that I condone such stealing). TL;DR: politics will always be a part of video games, so anyone demanding they’re not is wasting their breath - or rather, their time writing diatribes online.

However, there’s still a sticking point. Big-budget games really do struggle to - as Olsson says regarding the heroes and villains of the Wild West - wear their politics on their sleeves in the same way indies do - indies like Papers, Please, Disco Elysium, and Not Tonight. Says the professor: “Historically themed video games can be vital in generating curiosity on the part of gamers… But I’m sceptical that major blockbuster AAA games will actually ‘teach’ much history. They’re ultimately more interested in feeling than knowing, and excitement and drama over thoughtfulness. But there is enormous potential in teachers harnessing the passion that millions of gamers feel for their games.”

And Constant shares this opinion on bigger studios’ reluctance, still, to outwardly celebrate that their new game is a political piece of expression: “Publishers, platform holders and investors typically shy away from anything that could affect sales, deals and promotional opportunities, and being explicitly political can do that. Combine that with how difficult it is to make games, especially obtaining funding, and it’s understandable game devs don’t want to make things harder for themselves.” Basically, it’s all about the money - and when smaller games have tighter margins, coming out and voicing support for a certain politician, a perspective, rights for a section of people previously oppressed, can mean lower sales, however abhorrent those potential buyers’ own political leanings might be. Assuming, that is, their claims that they would have otherwise bought this game are sincere in the first place. Probably not, huh.

Advert

- - -

“It’s good to be anti-fascist in everything you do, including when you make games.” - Tim Constant

- - -

“What we want you to come away with is an understanding of why all these different groups fight, or groups like them, and to have empathy for, I think, all of them, and what puts them in this situation,” is how Minkoff rounds out the Game Informer interview on Modern Warfare - and right there is Olsson’s point on AAA games aiming for feeling first and knowing second. Is this virtual conflict fun? Obviously that’s a huge selling point of any video game - but does the reality that supports the fiction always need to be so shrouded in smoke and mirrors? Must the loud part always be spoken about so quietly? Can we not learn to say: hey, we’re totally referencing this real-world horror. This war that’s unfolding just over there, four pages on from where your home is in an atlas. This atrocity, these politics. It can still be A Fun Video Game - just look at what Spec Ops: The Line achieved. Well, maybe, but would it change anything about how we see the world? Can video games really change the world, like so many suits on stage at huge corporate gaming events have told us?

“For games to change the world, they have to be able to teach empathy with people unlike the person holding the controller,” says Olsson. “That means foregrounding a wide range of protagonists with a diverse set of worldviews.” No arguments there. But what about Constant? “No,” he says, bluntly - games cannot change the world. “Direct action, voting, protesting, volunteering is more important. Otherwise with the amount of games launched every year we should be living in a utopia. But it’s good to be anti-fascist in everything you do, including when you make games.” No arguments there, either.

Thanks to Tim and Tore for speaking with us. Find information on Tore Olsson’s work and his publications here. Find PanicBarn on Twitter here.

Topics: Call Of Duty, Interview, Indie Games, Red Dead Redemption 2