Every gamer remembers their first “oh shit” moment. That beautiful, life-changing moment that punches you in the gut and shows you how transformative, how immersive a good video game can be.

For some, that moment might have been getting all 120 stars in Super Mario 64, or stepping out onto Hyrule Field for the first time in Ocarina Of Time. For others, it could be the train sequence in Uncharted 2, or Mass Effect 2’s Suicide Mission.

For a lot of gamers around my age, it was the D-Day mission in Medal Of Honor: Frontline that glued our jaws to the floor. While the Medal Of Honor franchise has long since been forgotten about in a world dominated by Call Of Duty and Battlefield, there was a time when nobody did gritty, explosive World War II campaigns better.

Advert

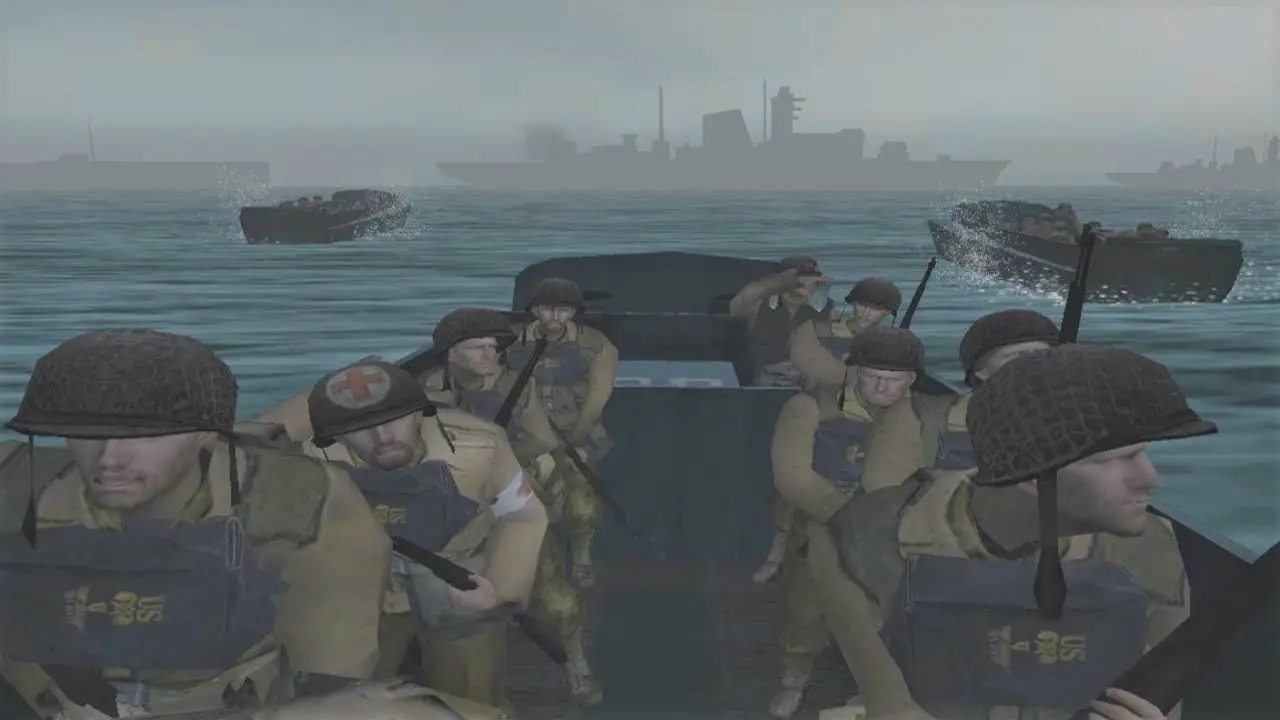

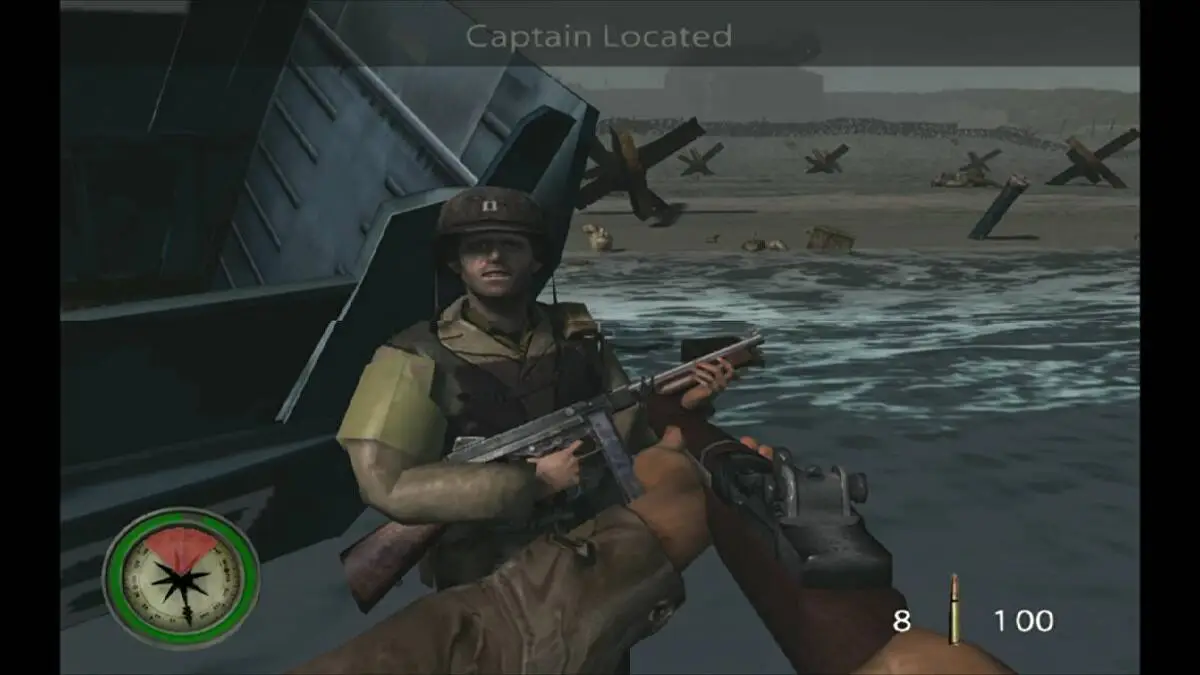

2002’s Medal Of Honor: Frontline begins in a flurry of bullets and chaos as the player makes their way towards Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. Fellow soldiers fall around you’re launched into the icy water before emerging onto land, although you’ll wish you’d stayed in the sea. The beach itself is sprawling - shockingly huge for an FPS level at that time - and absolute mayhem. Bombs and bullets fly everywhere, and all the player can do is sprint towards the objective, occasionally take cover, and hope for the best. Shooters, particularly console shooters, had rarely been so terrifyingly visceral.

‘Your Finest Hour’ is a level that has stuck with players for 20 years, and was for a long time often hailed as one of the best opening scenes of any video game - certainly any first-person shooter. But as it turns out, D-Day was never actually supposed to be in Frontline.

Chris Cross, lead designer on a number of the original Medal Of Honor games including Frontline, tells me over email that D-Day’s inclusion in the game was a direct response to the immense popularity of a very similar Omaha Beach level in the PC-only Medal Of Honor: Allied Assault, which had released just a few months earlier.

The Allied Assault level had been shown around internally at first, and the overwhelmingly positive feedback cemented the Frontline team’s decision to include something like it in their own game. Cross had his reservations initially. He tells me he pushed back against the decision as there were some “story gymnastics” that they had to pull off to make it work in the context of the larger Medal Of Honor story, getting certain characters who shouldn’t have been there into place.

Chronologically, series protagonist Jimmy Patterson was in the hedgerows of Normandy in the original Medal Of Honor just a couple of nights before D-Day rescuing a G3 officer. Obviously, that means it didn’t make a world of sense for him to then be arriving on Omaha Beach by boat. But it all worked out with just a little bit of quick thinking and some slight liberties.

“We found a way and most people didn't notice,” Cross says. “Including D-Day was the right call for the product. I just wanted to make sure we didn't cause some dissonance in the audience.” But making D-Day work in Frontline on a narrative level was just the beginning of an incredible challenge that involved Cross and his team using every trick at their disposal.

“Man, making D-Day work on a PlayStation! At that time we had an 8-12 NPC limit due to RAM considerations,” Cross remembers. “We had sub teams that owned each ‘Mission Group’ of Levels. The D-Day team was really on point and turned around a mission that we didn't even have planned in a short amount of time. So much custom work went into that. Making believable waves was one of the hardest things. There aren't even real enemies in the bunkers shooting down at the player. These were automated bullet emitters with a mannequin in case you zoomed in. Lots of crazy hacks we did to make that whole mission work.

“But once we knew we had to do it there was just problem solving. I think the first half of making it there were a lot of doubts but those went away the first time the Higgins boat ramp opened and the animation sequences played.”

“It was an extraordinary challenge,” agrees Frontline’s lead animator Sunil Thankamushy. “How do we show multiple people like literally hundreds of people rushing up the beach?! And the trick was, obviously, smoke and mirrors. We’d always think of the Pirates Of The Caribbean ride in Disneyland, where things are made to appear a certain way. In scale, scope, etc. Using smoke and mirrors, it’s pure showmanship! For D-Day we tried to apply that to create the feeling of a huge assault, but it really was just a handful of characters walking up the beach. So it's all about how it was staged.”

Sure enough, revisiting the iconic mission now with this in mind and actually counting the number of characters present at any one time, you’ll notice it’s much less crowded than you remember. Thankamushy explains that the team emphasised a lot of the clever tricks and workarounds with sound design and gameplay that were basically designed to be as intense as possible. In other words, they threw everything at the player to maintain the illusion.

One of the more obvious inspirations for the level was, of course, Steven Spielberg's WWII picture Saving Private Ryan - but Thankamushy actually remembers working with one of its stars: Captain Dale Dye.

For those who might not be aware, Captain Dale Dye is a Marine veteran of the Vietnam war, as well as founder and head of Warriors, Inc., a technical advisory company that works with studios on portraying realistic military action in movies. Dye worked on everything from Band Of Brothers and Saving Private Ryan all the way through to the Medal Of Honor games.

“He would come to us occasionally and give us lectures and training, basically explaining how the mission was actually carried out,” Thankamushy recalls.” He had the task of trying to turn us into World War II experts, on some level. Because if we had to do this, we had to do justice to the greatness of that day.”

The Medal Of Honor franchise is largely ignored these days, save for a badly reviewed and mostly forgotten VR game that released back in 2020. But there are still fans who will never forget the impact of games like Frontline and its undeniable ambition and ability to tell epic stories that we just weren’t used to seeing in FPS games at that time. Certainly, I don’t think it’s unfair to argue that Frontline and its siblings paved the way for more story-driven Call Of Duty adventures like Modern Warfare and World At War.

It’s little wonder, then, that fans are still desperate to see the franchise return in some form. Cross has personally been hugely supportive of fan projects over the years, even offering to lend his expertise and advice at various points.

“I'm happy to have a personal impact on people,” Cross tells me. “That's the whole point of game design. It's very validating. We didn't use social media like we do now in those days so basically I have no idea how people personally were affected by our designs in those days.”

As fondly remembered as Medal Of Honor might be, at least to a certain generation, is there really a place for it in a world where the console FPS market is effectively dominated by two juggernaut franchises?

Cross certainly isn’t sure that Medal Of Honor would work if it attempted to compete with Battlefield and Call Of Duty. Instead, he tells me if given the chance he’d embrace the series’ roots as a spy game, leaning more heavily into sandbox levels and stealth in the vein of Assassin's Creed or Hitman.

“Medal of Honor at its heart was a spy game,” the developer says. I would lean back into the spy aspects and not the shooting aspects. If we remastered Frontline, I would go back to a single objective for each mission, make the levels open world, and let people finish the objectives however they wanted. Really lean into a solitary survival experience and de-emphasize the combat as only a necessity to finish the mission if there wasn't a stealth or spy way to do it. Take a lot of inspiration from the Assassin's Creed series.”

Conversely, Thankamushy believes that Medal Of Honor would be able to hold its own under the right circumstances. It simply comes down to having the right people for the job.

“As a good friend of mine and a producer told me a long time ago, good teams are what make good games,” he explains. “People are what make games, not technologies or anything else. And I completely believe that chemistry in a team is really what makes for the right mix of, of nurturing talent, resources, money, and content ,and turn it into a good game. Of course Medal Of Honor still has room for new releases. It's all about the team.”

Topics: Retro Gaming, Battlefield, Call Of Duty