Inon Zur is one of, if not the most, prolific composers working in the gaming industry today. With a huge backlog of iconic scores to his name, there’s a good chance any gamer worth their salt will have had his songs in their heads at some point or another.

The American melodist is known for his work on the likes of Dragon Age: Origins, Prince of Persia, Fallout 3, 4 and New Vegas, Crysis, the upcoming Starfield and many, many more. We sat down with Zur to discuss his work on the new game Syberia: The World Before, which releases on March 18 alongside the vinyl release of the soundtrack.

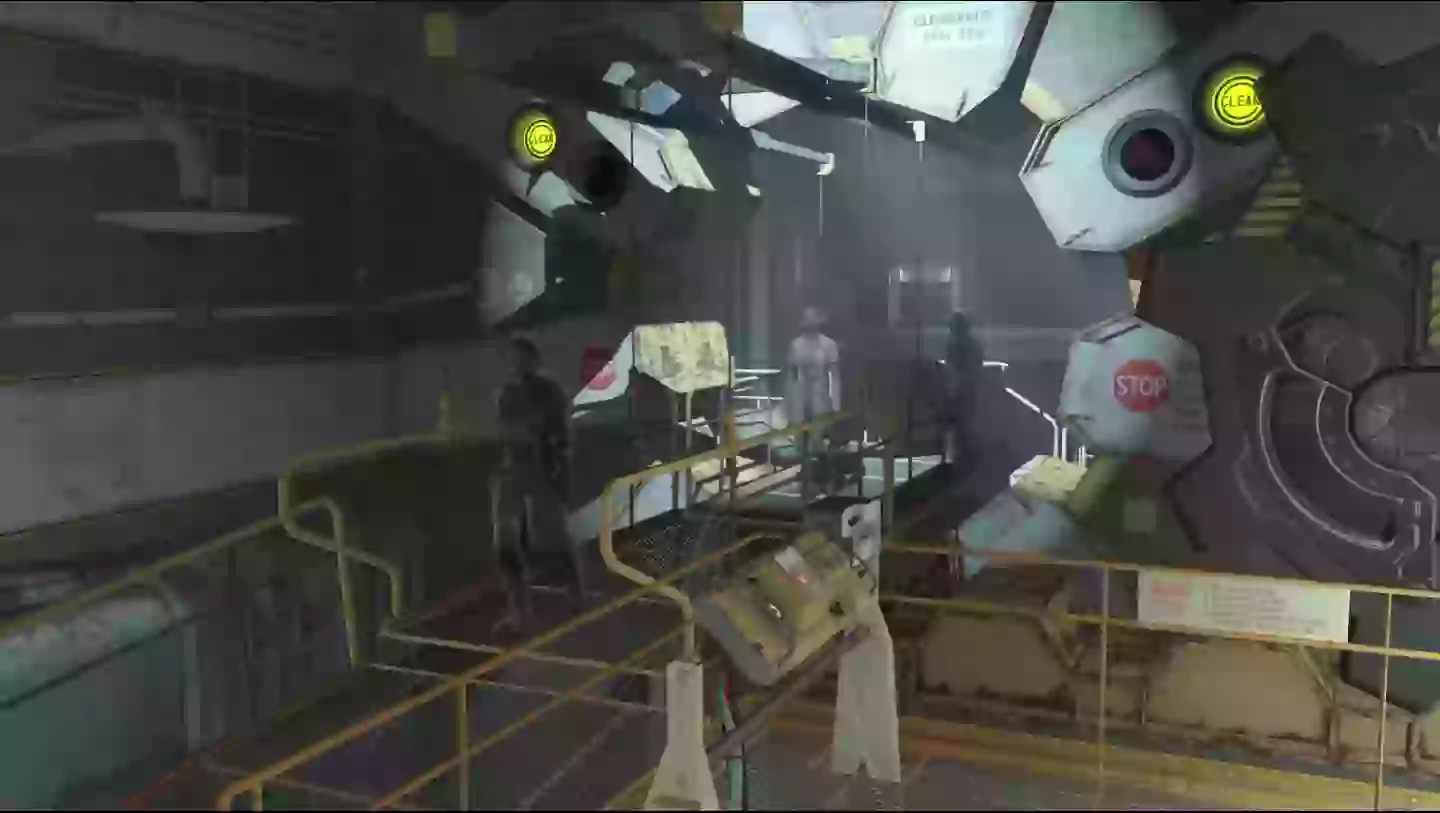

Before we get going, check out Zur in action performing the main theme from Fallout 4.

Our talk with Zur meanders through a number of topics, including his creative process, how to really nail the tone of a video game through its music, and what the inside of a Fallout Vault sounds like.

Advert

GAMINGbible: Tell us about your process - how you get ready to write a piece? Are you often given free rein on what you want to do? Or do you have certain ideas and motifs fed to you?

Inon Zur: Well, at the beginning of every project, but specifically if it's a new project, I’m always involved. I like to know as much as I can about the project first and foremost. If I can come over to the studio and meet the people behind the game, look at footage, gameplay. If the game is in later development then I'd like to actually play the game. Get the feel of it really, before I'm even thinking about [the music].

Then we go into the more creative meeting, which is what kind of music the developers envision. So I have the three Ws, right? ‘Where’, ‘what’ and ‘why’. And the ‘why’ is actually the most important one. Because I want to know: what drives the characters in the game? What drives the plot? And I want to know how to drive the player themselves.

So let me just give you an example. When I worked on Fallout 4, (Bethesda Game Studios’ director) Todd Howard told me about the story of the game, and that it was a very intimate story about you looking for your son. So I said, how about piano? Because piano, to me, brings intimacy.

Advert

GB: It's interesting you say about how the piano came to be used as an expression of searching for your son. Does that feeling come often, where someone is describing the game, or you play the game, and you hear the music that you want to make for it?

IZ: Yeah, very much so. Let's consider the ‘when’ and ‘where’, and let's take Syberia: The World Before, as an example. We're talking pre-World War Two, we're talking about Europe - that already brings us into a very specific place in time. So I will think of music that will bring the player into this era. One of the characters is a classical piano performer and, obviously, we want to feature the piano to support her character. So these things are basically almost automatically screaming for me to write them.

GB: I was reading an interview where you said that oftentimes you want to talk to the sound designers of a game to get a feel for what’s happening in a scene. The example you used was, if there's an engine running in a game’s scene, you'll find out what key an engine runs in and you’ll write to that key. Can you explain your thought process behind that?

Advert

IZ: The best way for the expression of music in gaming, I always say it, is that you don't really hear it, you feel it - it creates emotion, but you don't really notice it. There are lots of techniques to do it, but one is to really take into consideration the other background noises and sounds. Now, the player is not going to be aware, but something will feel right, or something will feel wrong and they will never really know why. But we know. So for example, in the case of the engine that hums in the key of E, if I would write in F, which is a half step above E, it will feel tense, weird, and uncomfortable, and I might well want to create this feeling.

The thing about it is, it's all about awareness. Music is a totally separate part of the soundtrack, because we have dialogue and sound effects, and more. If the music works with those things it creates a wholesome experience. But if it does draw too much attention to itself, it is actually distracting the player from what's going on, and this is the last thing we want to do.

GB: So with games like Fallout and Prince of Persia, they're based on fantasy and on things that don't necessarily exist. How do you then put that into the process?

Advert

IZ: It’s a great question. Let’s use Fallout as an example. We know that we are inside a parallel universe where, in the 1950s, the world [as we know it] just ceased to exist - but now we are in the 2100s or whatever. There's a whole new reality that came to be. For this, I think, the last music that we knew was in the ‘50s, right? Now, from the ‘50s, there was like a diversion; an extraction from this [music], and it went to a very unknown place. Everything that used to be played by the violin, for example, will be improvised by a primitive instrument. Let's assume that all the violins, including all the expensive Stradivarius, just cease to exist. Now we need to play, I don't know, the kitchen sink or something that was left around here. Now, in Fallout specifically, I created instruments that were born in this parallel reality. We help the player be inside this universe by creating these sounds that are being played on an instrument that literally does not exist.

GB: So what does the inside of a Vault sound like to you? Taking into account that you're bringing together instruments that you've created to make that ambient sound.

IZ: It’s a very interesting question because the Vault is a stuffy place, but above all the Vault is very metallic, there's a lot of metallic elements there. Now, here's the trick - I can write a lot of music with metallic elements, but then what will happen? It will merge with the real sound effects that are also metallic and it's going to create confusion. The metallic sounds usually are very sharp, so we create pads that are electronic but they will feel metallic. They will not have the attack, or the percussive sound of the sound effects. It will sound somewhat technological, it will sound somewhat metallic, but it won't be the actual metal hits.

Advert

GB: So what does Syberia sound like, using that same example?

IZ: Just imagine Berlin in 1937. People are walking around, and somewhere in the distance there is a lone violinist, just playing and collecting coins from nice people. There are some people singing in choirs in a church, the music that people know. I will create music that basically complements [these early 20th century sounds]. And the way to do it is to write something that will sound classical. When the player walks around Berlin, they will hear classical-esque music, it will put them right where I want them to be. Obviously, classical music can be happy, it can be sad, and it can be scary; but again, the elements - orchestral elements, solos, classical soloists - this is what really puts us in this world. With Syberia: The World Before, it's so beautiful and amazing I wouldn't even say it’s a game. It's an experience because the story is so compelling and I had to stay in a very realistic place. When I wrote [the soundtrack] I really took inspiration from Rachmaninoff, from Debussy, from Stravinsky, from composers that we think that these people in this era knew.

GB: When you choose a project, is it important to take into consideration how much personal gratification you’re going to get from it?

IZ: Oh, for sure. Since I was young my parents listened to classical music. I've been introduced to other types of music like jazz and rock and other styles way later in my life, but I’m the most in touch with classical music. So composing the music for Syberia: The World Before was really a dream come true. Because it basically had me just write classical music - this is what I've learned, this is what I've studied in Israel and here in the US, and this is what I love to do. I'm not saying that I don't like to do other styles. I'm very excited, for example, about the combination of electronic music and symphonic music in Starfield, which I cannot really talk a lot about. But it is also something that is very much like a discovery for me. Or Outriders, which came last year and was very, very harsh and electronic - almost like a dubstep orchestra, shall we say!

GB: Do you find it hard to switch off, for example, when you’re out for dinner, and you hear a motif that you really like, are you thinking, ‘Oh, I wonder if I can just change the pitch or change the note slightly.’

IZ: That happens a lot and I find myself singing to my cell phone and recording myself! Even sometimes just while driving and thinking about stuff, I suddenly have a piece that is with me for 24 hours, even when I am asleep! Today I had a dream, for example, that I'm playing guitar and singing. Now, I hardly can play the guitar and definitely I'm not a singer. But still, music is part of my life always. That said, the time I spend in the studio is very concise. My daily routine is almost rigid, and it's important for me. So I will start at eight and I'll finish at five, and if I don't really have to I will not go back to the studio. I'll spend the time with my family, but that’s not to say that music just goes away.

GB: That’s surprising. Surely you have moments where you’re in the middle of inspiration and you have to see it through?

IZ: I must admit that sometimes, especially when I'm working on main themes, which are sometimes the biggest challenges and hurdles, I will spend a little bit more time in the studio. But again, on a regular basis, I would really limit myself to a maximum of nine hours in the studio and that's it. I think it's very important to every composer to know when to stop - when to go out, when to do other things. Which are inspiring and contributing to who you are as well.

GB: Yeah, that's a great point, I would imagine a lot of your inspiration just comes from life. If you’re out doing something and you're experiencing something, do you kind of write your own music to what you're doing in your head?

IZ: No, but I must say that earworms are the way I live. There's always one earworm if I'm jogging, or walking or cycling. There is always a beat to what I do.

Syberia: The World Before will release on Windows on March 18 with console releases coming later in the year. The digital version of the soundtrack is also already out, and vinyl copy will be available March 18 alongside the game.

Topics: Fallout, Starfield, Prince Of Persia, Dragon Age